Posted on November 14, 2024 by Sean M. Wood

Actuators are everywhere. They’re in your car, in stores, and on job sites. They’re ubiquitous. Simply put, actuators convert energy into motion. The easiest to relate to is the brakes on a car. You push the brake pedal, and the brake fluid flows to the brake calipers, which close on your discs.

Actuators are big business in the military, operating all manner of hatches, doors, gears, lifts, valves, and more. For the Navy alone they’re a $2.8 billion business according to Fortune Business Insights.

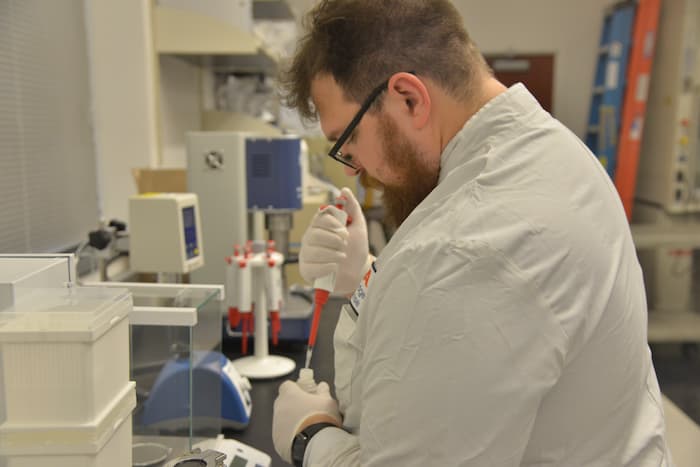

Mechanical Engineering Professor Dr. Cody Gonzalez and students in his Design of Actuators Robotics & Transducers (DART) Lab recently won a $449,000 grant to develop a new type of actuator. This work relates to Department of the Navy award #N000142412602 issued by the Office of Naval Research. These new actuators would be silent and self-powered by lithium-ion batteries. They move by converting electrochemical energy into motion.

“We’re looking for the right chemical combination to introduce into lithium-ion batteries so we can induce them to expand in a controlled manner. We also have to encase them in a way that maintains their durability as they’re expanding and contracting and so they maintain their charge.” - Dr. Cody Gonzalez

Usually, it’s dangerous for a battery to bend or expand. You would have a problem if your phone or laptop battery started to swell. But when it happens in the DART lab for Gonzalez and his talented team of research assistants, that’s progress.

“Bending a battery like this has never been done before, and we’re looking at ways to do it and control it,” doctoral student and DART Lab President Bryan LeBlanc said. “We’re not only trying to control its movement but use it to do work. We want to be able to push on things or use it to crawl around on a table or something like that.”

For strategic reasons, the Navy wants actuators that power themselves. They are quieter than traditional actuators. Watch any submarine thriller — “The Hunt for Red October,” “Das Boot,” “Run Silent, Run Deep,” “Crimson Tide” — and you will understand why.

The types of actuators currently used by the Navy include pneumatic, hydraulic, electric, mechanical, hybrid and manual. They have an outside power source, which can make them potentially noisy. The team has made batteries that can move like an inchworm and expand and contract. Gonzalez gives them plenty of room for experimentation.

“He's entirely open to new ideas and concepts. He's been able to help us, and we've been able to help him create an environment that allows us to continue to try and do the unthinkable.” - Bryan LeBlanc

DART Lab Vice President and mechanical engineering student Benjamin Gregory was determined to become a nuclear engineer until he met Gonzalez.

“I started researching batteries and found that I really enjoyed the topic and learning about all the chemistry of how they work,” Gregory said. “This project directly resulted from that research as I found a few applications that might work for underwater batteries, and the Navy might be interested in them.”

Gonzalez is the principal investigator on the grant, but it includes spots for two graduate students and two undergraduate students. Rebecca Lima, a second-year mechanical engineering student, is leading a team that evaluates component materials in an effort to extend battery life.

“I had little knowledge about lithium-ion batteries, but I’ve since gained expertise in battery fabrication, electrochemistry, and material characterization,” Lima said. “More importantly, I’ve developed essential professional skills such as collaboration, problem-solving, and persistence. I couldn’t be more grateful to Dr. Gonzalez for allowing me to prove myself as a student serious about research.”